HISTORY

The History of Pisco

This story begins with a blunder. While seeking a new route to the indies, Christopher Columbus arrived in a New World, giving way to an intense exchange of products, cultures, and visions. Spanish colonizers brought European plants and animals with them to ensure that they would have access to their regular food products during their life in the New World.

Mirrors, salted meat, firewood, legumes, and grapevines were some of the first products that they began to exchange for gold, tobacco, animals, and other exotic products from the American continent.

Spanish grapevines adapted surprisingly quickly to Chile’s fertile lands, yielding much more wine than was required to celebrate Mass and support the Evangelical process. This was the birth of an emerging wine industry in the Spanish colonies, particularly in the Viceroyalties of Peru and La Plata.

In 1549, the Chilean city of La Serena was refounded, and local residents began to plant the first grapevines in the area. This activity would later extend to the Copiapó, Huasco, Elqui, Limarí and Choapa Valleys.

The unique characteristics of these territories allowed for the production of high quality wines with intense sugar. It was precisely this sugar that made it difficult to transport the sought-after product because it deteriorated quickly.

To ensure that it was adequately preserved and reduce the volume that needed to be transported, producers began to extract the alcohol from the wine. This process, known as distillation, was enhanced by the presence of copper and artisans who specialized in this work known as fragüeros. They created the copper still, which continues to be the very soul of pisco. María de Niza registered the first still in the Southern Cone of South America in Santiago de Chile in 1586.

The aguardiente was bottled in baked clay pitchers that came to be known as “piscos.” These vessels were made by indigenous residents of the area that is now part of Peru and Chile. They made long trips to deliver supplies to vast mining areas in the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Pisco was born in the heart of the Elqui Valley near the Claro River south of Monte Grande. The decision to use the word “pisco” to refer to the grape aguardiente that was made in the area was made at Hacienda La Torre. It was formally registered in a document written by the Spanish Imperial Scribe in 1733. This document is now housed in the La Serena Judicial Fund of the National Archives in Santiago de Chile. The text documents the existence of three jugs of pisco in that vineyard. The custom of using the word ‘pisco’ to refer to local aguardiente soon became common thanks to the local haciendas in Diaguitas and other towns in the Elqui Valley.

Hacienda La Torre was created by Don Pedro Cortés y Mendoza, also known as the “Hero of Tongoy” because of his valiant efforts to fight off pirates in 1686. Don Pedro encouraged his neighbors to create a winemaking cluster in the eastern part of the Elqui Valley 20 leagues east of La Serena in response to the threat on the high seas. Haciendas were thus built in the narrow stretch of land between the Claro River and the Andean foothills, and they had all of the equipment and facilities necessary to make wine and distill aguardientes.

This area presented significant strengths such as its distance from the sea, which placed the haciendas outside of the pirates’ reach. This distance guaranteed the safety of the residents’ investments and encouraged local landowners to transfer their capital and investments to this location.

The altitude of the territory (1,200 meters above sea level) was an important advantage for distillation because the temperature required to reach the boiling point is inversely proportional to altitude. As such, stills are more efficient under these conditions. Furthermore, the thermal variation in the mountains has a positive impact on the vegetable physiology of the grape vines. The valley has a special microclimate, and its fertile soils are highly valued for the production of fresh fruit.

Coquimbo’s winemakers led the efforts to diversify Chilean viticulture. While the rest of the country focused exclusively on growing Uva País, residents of Coquimbo started growing Moscatel de Alejandría in the early 17th century. The local grape varieties that developed over time are the result of the coexistence of these two types of grapes and cultural and natural selection processes.

This produced a rich variety of pisco grapes: Moscatel de Austria, Pedro Jiménez, Moscatel Amarilla (Torontel), and Moscatel Rosada (Pastilla), among others.

Hacienda La Torre was also home to the first oven used to bake clay vessels in northern Chile, and this is where the area’s first still was installed. These innovations were later imitated by other local landowners, and northern Chile quickly became a dynamic winemaking area. The inventories of the National Archives reflect the investments made in these haciendas between the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

The notarized will of Doña Gerónima de Rivera y Rojas in San Ildefonso de Elqui dated June 9, 1950 states that she owned 9 jugs of “pisco.” In 1758, a jug of “pisco” was listed in the will of Don Crístobal Rodríguez.

Following the death of Don Pedro Cortés y Mendoza in the late 17th century, his son, Don Juan Cortés y Godoy (1717-1727) followed in his footsteps. The work was later continued by the former Magistrate of Coquimbo, Don Marcelino Rodríguez Guerrero (1727-1733).

DENOMINATION OF ORIGIN

The GENESIS OF the denomination of origin of PISCO

The Chilean Central Valley also had a tradition of developing aguardientes, which were generally distilled based on sediment and marcs while piscos are made from aromatic white grape wines. In an effort to improve their sales, some merchants in Santiago, Valparaíso, and Concepción decided to label local aguardientes as pisco, which created a series of disputes and conflicts that were part of the “Pisco War.” “Piscos” made in such diverse locations as Santiago, Chillán, San Felipe and Limache were presented at the 1872 Expo in Santiago.

The Norte Chico producers made their voice and opinions heard before the national government through their representatives. The issue was discussed at the highest levels. For many years, the Chilean government gathered the information it would need to solve the problem.

Finally, on May 15, 1931, President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo issued Decree No. 181, establishing Denomination of Origin for pisco, which was defined as “brandy that is produced and labeled in consumption units in the III and IV Regions of the country through the distillation of genuine potable wine from the grape varieties listed in Decree No. 521 planted in said regions.”

The main argument of Decree with Force of Law No. 181 was the prestige and fame that Norte Chico producers had achieved through their efforts to develop higher quality products over the years. The World Expos and registered trademarks contributed to this fame, which facilitated the compilation of sufficient information to provide a basis for the creation of the Denomination of Origin for pisco. From then on, the name pisco could only be used for aguardientes crafted in the Copiapó, Huasco, Elqui, Limarí, and, later, Choapa Valleys. This was the process by which the first Denomination of Origin in the Americas was created.

PISCO GRAPES AND THE PISCO PRODUCTION PROCESS

pisco grapes

Pisco is the legacy of a centuries-old distillation tradition. Its production brings together history and modernity, maintaining the highest production quality standards whether it is completed in a small boutique distillery or a large corporation. These standards are based on two important elements: the Denomination of Origin of pisco and the raw materials used to make it.

Pisco’s Denomination of Origin reflects the factors and characteristics that make the distillate a product that is intimately connected to the geographic and cultural conditions of the Copiapó, Huasco, Elqui, Limarí and Choapa Valleys. Pisco grapes are also critical to the process, and emerged thanks to the coexistence of various types of grapes that gave life to new unique and endemic varieties in these fertile soils.

There are approximately 10,000 hectares of pisco grapes in Chile, and Moscatel Rosada, Moscatel de Alejandría, Moscatel de Austria, Torontel, and Pedro Jiménez are grown in most of them. There are also other less frequently used pisco grape varieties, such as Moscatel Temprana, Amarilla, Canelli, Frontignan, Hamburgo, Negra, Orange, and Chaselas Musque Vrai. These grapes grow just beyond the desert in areas with cold nights and plentiful sunlight, which gives them a high level of sugar.

It takes approximately 3.5 kilos of pisco grapes and months of work and dedication of nearly 3,000 farms to make a single bottle of pisco. Each bottle is thus the fruit of the efforts of thousands of small- and medium-scale farmers. The pisco industry maintains strict quality standards in accordance with Decree with Force of Law No. 181 (1931). This decree awards pisco its Denomination of Origin, the second oldest in the world and the first in the Americas. As such, Chilean pisco and its production process, geographic specifications, and especially its name are protected by law.

thE PISCO PRODUCTION PROCESS

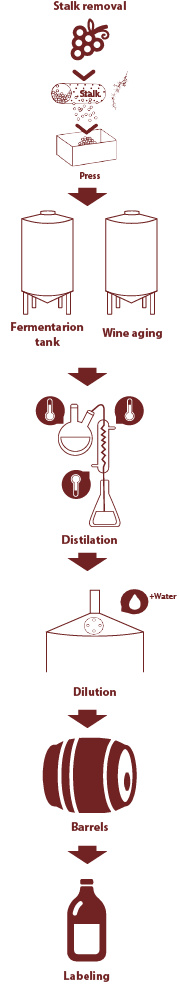

Pisco production consists of four main phases:

- the growing and harvest of pisco grapes

- vinification

- distillation

- bottling in consumption units.

Pisco’s Denomination of Origin establishes that all of these phases must be completed in the pisco region.

Pisco grape harvest begins in mid-February each year. It generally starts with the earliest variety -Moscatel de Austria- and concludes with the grapes with the largest cycles -Moscatel de Alejandría and Pedro Jiménez. The date of harvest is determined by the likely alcohol level of the grape in the bunch, which must be equal to or greater than 10.5º P.A.

The grape is then transported to the distilleries and waste like leaves and stalks is removed. The grape is then pressed to extract its juice, which will be vinified as a white wine under controlled temperatures. The vinification process takes an average of 30 days, depending on the level of technology used in the process and the yeasts used to ferment the pisco.

Once the wine is made, the distillation process begins using copper stills because this material contributes no flavor to the alcohol, is resistant to acid, and conducts heat well. The still is a device used to distill liquids through a process of evaporation by heating followed by condensation by cooling. It was invented by the Al-Razi, a Persian inventor, in the 10th century to make perfume, medicine, and alcohol from fermented fruit.

Pisco wine is poured into the still and brought to the boiling point to separate out and capture the alcohol. The alcohol obtained through this process is divided into three parts: the head, the heart, and the tail. The heart is the purest part, and this is what is used to make pisco. The master distiller decides where the heart in the distillation begins and ends, which means that the final product will undoubtedly bear his or her mark.

The heart can be distilled once, twice or even three times depending on the level of purity and organoleptic properties sought. The alcohol obtained from the foot of the still has an alcohol level that can fluctuate between 60° and approximately 73°. This is why, as is the case with distillates like whiskey or vodka, the final alcohol level is adjusted using demineralized water.

The distillation of wines from each season begins immediately after the wine is ready and must take place before January 31 of the following year to avoid coinciding with the fruit from the next harvest. After distillation, the alcohol should rest for at least 60 days. This process takes place in steel tanks or containers made from a local wood called ‘raulí.’

Once the alcohol is bottled, it can be called pisco. Given that it has not aged in active wood, this pisco is transparent.

In the case of aged piscos, the alcohol is submitted to an aging process in wood barrels. The most popular woods used for this process are raulí, American oak, and French oak. This process gives the pisco a woody flavor that pairs very well with the product’s grape flavor. It also gives the pisco an amber color that becomes more intense as the pisco ages.